The belief in a supernatural source of evil is not necessary; men alone are quite capable of every wickedness1.

Мы рождены, чтоб сказку сделать былью, преодолеть пространство и простор2.

The present study is part of a larger research project that analyzed the language of the classic Russian novel The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита) by Mikhail Bulgakov on the phonological, lexical, semantic, and discourse levels3.

This study offers a sign-oriented linguistic approach for the study of a literary work based on Edna Aphek and Yishai Tobin4, Edna Andrews5, Tobin6. I applied this approach to the analysis of different systems of language in order to confirm my hypothesis that there is an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural in Bulgakov's novel, sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between them.

As its etymology suggests, the word «supernatural» is defined by the word «natural»: supernatural denotes that which is above nature («supra» — from Latin «above»). It is something beyond the power or laws of nature, i.e. a phenomenon that cannot be explained by natural or physical laws is described as being supernatural. In my study the category of «the supernatural» covers such notions as «the unreal», «the abnormal», «the mysterious», «the phantasmagoric», «the unknown», «the fantastic». «The natural» as it is used in my work refers to «the normal», «the real», «the realistic», «the known».

The supernatural, the irrational and the fantastic have always been an integral part of Russian and Soviet culture. The folk tale, the «бытовая сказка», includes («нечистая сила» — «the unclean force» and its manifestations: «русалка» — «the mermaid», «леший» — «wood spirit», «черт» — «the devil»)7.

The works of Zhukovsky, Pushkin, Lermontov and Gogol are based on the use of the supernatural. Saltykov-Shchedrin, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Lev Tolstoi, the Symbolists, Aleksei Tolstoi continued Pushkin's and Gogol's tradition of using the supernatural.

It is characteristic of Russian literature that when the supernatural or fantastic is used it is almost always «a dramatization of Russia destiny in almost apocalyptic terms [...] the fantastic is more real than state-dictated reality»8.

The supernatural and the miraculous pervade all spheres of Soviet discourse of the Stalinist era. Popular songs asserted that «простые советские люди повсюду творят чудеса» — «simple Soviet people create miracles everywhere»9.

The mass media informed Soviet citizens daily about the «miracles of heroism» — «чудеса героизма», being performed by the Stakhanovites.

There was a system of politically correct connections, so that the two components of each linguistic sign10: i.e. the «signifier» corresponded with the officially allowed «signified». That is why free experimentation with the language of the arts was prohibited. A cliche-filled language was used on all levels of Soviet discourse, from poetry and fiction to newspapers and Party documents11.

Stalin was described in supernatural terms: all-knowing, all-powerful. Especially composed «folklore» provided Stalin with magical powers. «Stalin waves his right hand — a city grows in a swamp, he waves his left hand — factories and plants spring up, he waves his red handkerchief — swift rivers start to flow»12.

According to Andrey Sinyavsky13, to the ordinary Russian, this all sounded originally like nonsense language, devoid of meaning yet portending something mysterious and sinister, since certain letters (Cheka, GPU, NKVD, MGB, KGB) threatened life while others constituted its foundation, like some magic formula for reality.

Mikhail Bulgakov worked on his novel The Master and Margarita throughout one of the darkest years of Russian history: it was a period of vast party purges and the Moscow «show trials», a period of forced collectivization and the first five-year plan. These were the years when the secret police penetrated into all areas of life, years of the expansion of the system of «corrective labor camps», and the liquidation of the intelligentsia.

There is a mysterious atmosphere in the novel, because the most supernatural events prove to be realistic, while apparently totally realistic facts become phantasmagoric/supernatural.

People keep getting arrested, disappearing, and then they turn up again; objects move around and transport individuals here and there; things happen, people do not make them happen. This can be attributed to the supernatural (the devil), until we realize that the agent causing things to happen is the NKVD, rather than any unnatural forces.

I assume that the use of the juxtaposition and the interconnection of the natural and the supernatural in the novel is a device to expose the readers to the everyday life of Moscow in the 1930's. I will demonstrate how the language supports the message: an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural in the novel, sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between them.

I first carried out the phonological analysis, i.e. I focused on the analysis of the language of the natural and the supernatural within The Master and Margarita on the level of the sound system of language — phonemes.

While collecting the data I realized that there are not only two obvious groups of words: a group of natural («человек» — «a man», «носки» — «socks», «окно» — «window», «нежно» — «tenderly») and the group of the supernatural («чертовщина» — «devilish things», «привидение» — «apparition», «бесовский» — «accursed», «чудо» — «miracle»). There is a third category of words denoting the realms of the natural and the supernatural simultaneously («странность» — «strange thing», «потрясение» — «shock», «происходить» — «happen», «неожиданно» — «suddenly»).

The words in this group are polysemous; the polaric notions of the natural and the supernatural «converge» within the words of the group. In other words, the lexicon of both the natural and the supernatural straddles the natural and the supernatural.

The words in this group have specific distinctive phonological characteristics of their own. These words are semantically more complex, and they are more complex phonologically as well (e.g., there are more polysyllabic words in the third group — the lexicon of both the natural and the supernatural. In addition, there is: (i) a favoring of more complex phonemes containing additional articulators; (ii) a favoring of visible phonemes that can be seen and not only heard and (iii) a favoring of phonemes of a greater degree of aperture which are more visible and resonant.

Therefore, my claim that the natural and the supernatural are interconnected to a high degree of convergence was supported on the phonological level.

I then apply the methodological model of word systems to the analysis of the natural and the supernatural in the language of The Master and Margarita. I demonstrate how each of the word systems (with phonological, semantic, etymological or associative denominators) used by Bulgakov in the novel contributes to the message of the text.

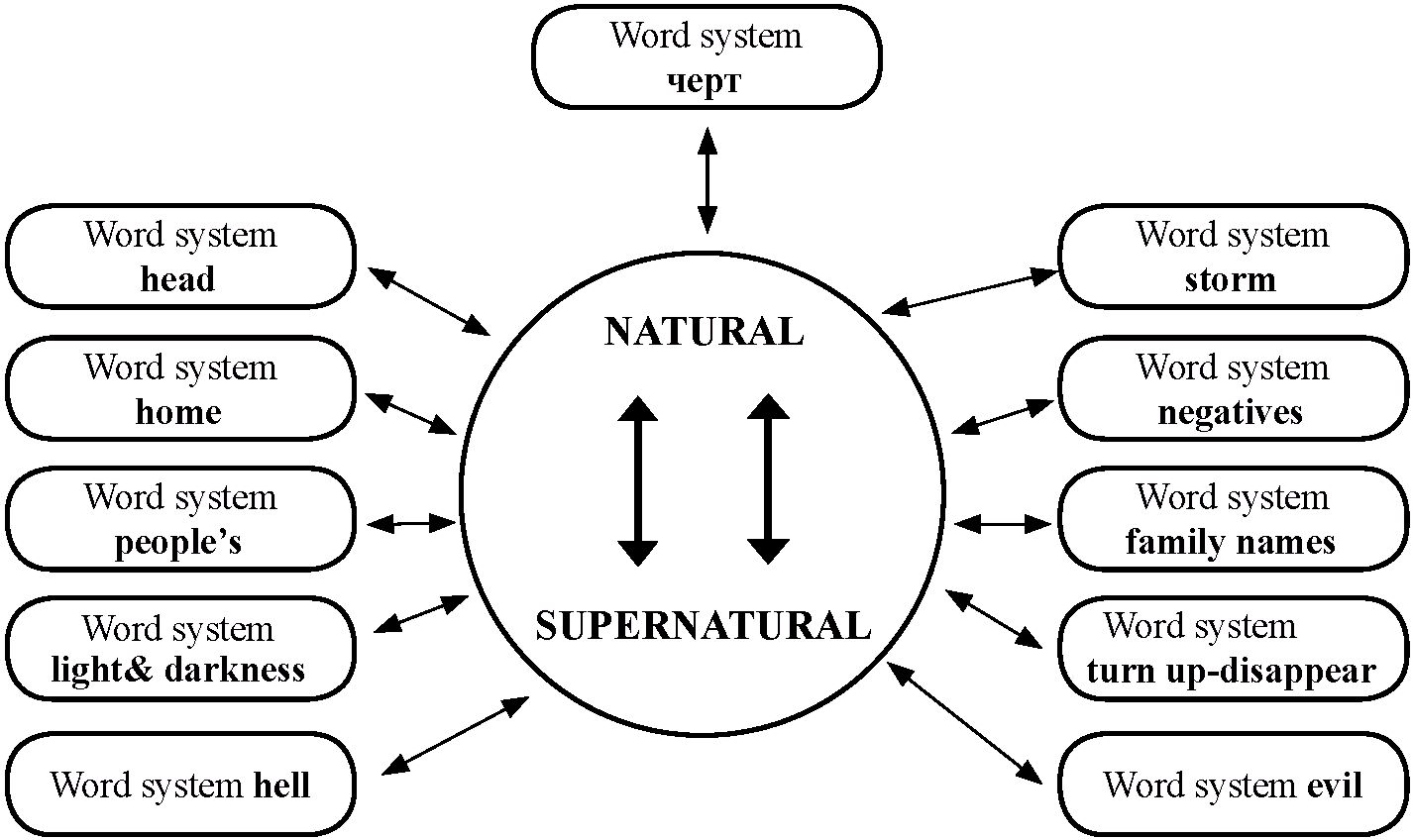

I follow Aphek's and Tobin's14 definition of a word system as a matrix of words within a spoken or written text with a common denominator, which may be semantic, phonological, etymological, folk-etymological, conceptual or associative. Analyzing the word systems of the novel, I demonstrate that there are words which are linked to each other and form a system or systems. This system / systems creates / create the message of the text. I have found at least eleven word systems in the novel through which the message is created — an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural (within the language of The Master and Margarita), sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between them. This convergence of the natural and the supernatural is illustrated schematically below:

Word systems in the novel The Master and Margarita

The word system associated with черт / дьявол — the devil

15The primary word system in the language of The Master and Margarita, which «nurtures the theme and message of the text»16, is based on the phonological, etymological, associative and semantic variations of the word черт / дьявол — the devil. These variations are present in every chapter of the novel; they are used so frequently that they become empty expressions without any associations with real devils. The черт / дьявол — related expressions can be subdivided into four subsystems:

• the semantic subsystem which includes the notion of the real devil as well as being a part of many colloquial expressions «черт их возьми» — «the devil take them»; «черт знает» — The devil knows».

• the phonological — etymological subsystem revolving around the root chyor which is both the root of the word «черт» as well as of the word «черный» — «black». In addition, other words that start with the sound /ch/, like «червонец» — «ten rubles», «человек» — «human being/person», may be indirectly related to this subsystem,

• the conceptual subsystem which includes words that create a feeling of fear and disgust connected with the devil, like «strange», «horror-stricken face», and

• the associative subsystem which includes words with negative features, like «repellent», «nasty», «dreary».

The word черт / дьявол in the word system in the Russian text is the peak of the pyramid whose sloping sides are semantic, etymological, phonological, associative, and conceptual variations.

Below I will demonstrate two of the mentioned systems.

The semantic subsystem

There are more than 80 expressions involving the name of the devil in the novel. The word черт / дьявол in Russian signifies both the notion of the real devil as well as being a part of many colloquial expressions and swear words. In everyday Russian such expressions as «черт их возьми» — «the devil take them» and «черт знает» — «the devil knows» are very common and it is not surprising that they are found throughout the novel. These and similar expressions appear in every chapter of The Master and Margarita at least once or twice, but in the chapters where the real devil appears, черт / дьявол-related (but empty) expressions are most frequent.

The appearance and motivated distribution of the phenomena discussed above occur in spite of the fact that the literal meaning of черт has been lost in these commonly used expressions. The fact that the most frequent use of the ordinary (natural) expressions is juxtaposed with the appearance of the real devil supports the message of the novel — an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural, sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to differentiate between them.

Moreover, the fact that there are several cases when the real devil himself makes use of the empty colloquial expressions, supports the message of the novel even more strongly (see table 1).

Table 1. The черт-related expressions used by Woland (the real devil)

| Russian Text | English translation |

| 1. «И на кой черт тебе нужен галстук если на тебе нет штанов? — воскликнул Воланд» (р. 524). | «And why the devil do you need a tie, if you are not wearing trousers?» exclaimed Woland (p. 218). |

| 2. «А, черт вас возьми с вашими бальными затеями! — буркнул Воланд» (р. 526). | «To hell w ith your ball practical jokes», muttered Woland (p. 219). |

| 3. «Помилуйте, сказал Воланд, на кой черт и кто его станет резать?» (р. 529). | «Just a minute» said Woland, «who the hell is going to butcher him and what the devil for?» (p. 222). |

Although черт / дьявол-related expressions are «empty» metaphors, without the notion of the real devil, it was an old Russian tradition to believe that if one used the name of the devil, the devil might appear. In the first chapter, where черт / дьявол-related expressions are used very frequently, the reader encounters the real devil. After Berlioz pronounces the most ordinary, frequently used (natural) expression «пора бросить все к черту и в Кисловодск» (р. 273) — «it's time to throw everything to the devil and set off for Kislovodsk» (p. 4) — Woland (the devil — the supernatural) appears.

In this part of paper I present only a limited number of examples to show the interconnection between an ordinary noun черт as it is used in everyday Russian (the natural) and the appearance of the real devil. In addition, there is another word in the Russian language for the devil — дьявол. Although the word дьявол is used only about twelve times in the text (whereas the word черт is used more than 80 times), both of these words (черт and дьявол) share the same characteristics in the novel — they are both used for the notion of the real devil, as well as appearing in commonly used expressions where the literal meaning is lost. Thus, черт / дьявол-related expressions support the message of the novel.

There are several examples in the novel that show that every time the name of the devil is mentioned the «empty» word is «materialized»: the devil himself appears. Here are three examples of such «materialization»:

1. The moment Margarita says: «Дьяволу бы я заложила душу» (р. 491) — «I'd sell my soul to the devil» (p. 190), Azazello answers her thoughts and brings Margarita to the devil and she not only accompanies him to the Ball but is ready to do everything to save the Master (another example of «materialization»).

2. When the Master exclaims: «Черт знает, что такое» — «the devil knows what this is», Margarita answers the Master: «Ты сейчас невольно сказал правду [...] черт знает и черт все устроит» (р. 637) — «You just spoke the truth without knowing it [...]. The devil does know [...] and the devil will fix everything» (p. 309).

3. Another example of such «materialization» of the «empty» word is in the scene in which Prokhor Petrovich's secretary says: «Я всегда-всегда останавливала его, когда он чертыхался. Вот и дочертыхался» (р. 458) — «I always tried to stop him when he used devil oaths! And now he is bedeviled himself!» (p. 159). And afterwards we see the scene where natural and supernatural events happen at the same time: the empty suit continues the work of the bureaucrat (Chapter 27).

The semantic subsystem of черт / дьявол-related expressions strongly supports the message of the text because this subsystem is found throughout the novel and overlaps with the notion of the real devil and the description of his actions, as well as including empty metaphors with the word черт / дьявол.

The phonological-etymological subsystem

This subsystem revolves around the root chyor and its phonological and etymological connection both to the word черт as well as to the word черный — «black». The word черт and the Russian word for black — черный have the same root.

The word черный is used about 200 times in the novel in the description of both the natural and the supernatural, which also supports the message of the novel (On the first page Berlioz has black frames on his glasses, Bezdomny is wearing black sneakers). In the following table 2 I present only four examples with the word черный.

Table 2. Examples with the word черный and words with sound /ch/

| Russian Text | English translation |

| 1. «очертил [...] очень черными красками» (p. 274).

2. «предчувствуя вечернюю прохладу, бесшумно чертили черные птицы» (р. 282). 3. «черный, как сажа или грач, и с отчаянными [...] усами» (р. 316). 4. «черная зависть начинала немедленно терзать его» (р. 322). |

«had painted the central character [...] in very dark colors» (p. 4).

«where the blackbirds were circling noiselessly in anticipation of the evening coolness» (p. 10). «pitch-black, like a crow, or like soot, and sporting a mustache» (p. 40). «He would soon become green with envy» (p. 46). |

It should also be noted that there are other words that start with the phoneme /ch/ in the novel. Although /ch/ is a marked sound (affricate), which appears very frequently in Russian, it is especially relevant when it is met in the word человек because it means «a human being / person». Человек (real/natural) is used more than 100 times in The Master and Margarita, the novel where one of the main characters is the devil / diabolic forces (the supernatural). In addition, I noticed that the word человек (the natural) occurs more frequently when the real devil is described, thus supporting the message of the novel. Table 3 presents only a limited number of examples where the real devil is described as a man / a human being.

Table 3. The word человек in the description of Woland (the devil)

| Russian Text | English translation |

| 1. «в алее показался первый человек».

2. «сводки с описанием этого человека». 3. «человек был маленького роста [...] особых примет у человека не было» (р. 275). |

«the first man appeared on the pathway».

«reports describing tins man». «he was short [...] he had no distinguishing features» (p. 5). |

The above example demonstrates that the word человек — «a man / a human being» (the natural) is used four times in this short description of the real devil (the supernatural). In other words, the fact that the devil is described as a man / a human being, even more strongly supports the message of the novel — an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural, sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between them.

Other words with the sound /ch/, like «червонец» — «ten rubles», «вечер» — «evening», etc. may be indirectly related with this subsystem. The following table 4 presents a limited number of the words with sound /ch/ in the text.

Table 4. Examples of the words with sound /ch/ in the novel

| Russian Text | English translation |

| 1. «была очередь, но не чрезмерная, человек в полтораста» (р. 322).

2. «Когда [...] вошел человек с острой бородкой и облаченный в белый халат, была половина второго ночи» (р. 322—323). |

«This door also had a line, but not a very long one, only about one hundred and fifty people» (p. 46).

«It was one-thirty in the morning when a man with a small pointed-beard and a white coat entered the reception room» (p. 54). |

The word system of черт / дьявол — «the devil» and words that are related phonologically, semantically, etymologically, and conceptually, are used to describe both supernatural events and events from real life. The natural and the supernatural exist simultaneously whenever Bulgakov uses the same word system in order to present real and unreal events.

The concept of strategies of communication was first presented by Aphek and Tobin in their semiotic analysis of the linguistic and extralinguistic elements of fortune-telling17 which many may believe to be related to the convergence of the natural and the supernatural as well.

Below I will demonstrate the use of incomplete or indefinite references to agents of actions as one of the strategies of communication / fixed patterns used by Bulgakov in the novel. The systematic use of incomplete or indefinite references to agents of actions (as a strategy of communication and its sub-strategies) intensifies an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural; as a result — the reader doubts whether the described events are real or supernatural. In addition, the reader can never be sure whether the agent is supernatural (diabolic forces) or whether the agent is real (the NKVD), which is never mentioned by name.

The following sub-strategies of communication are used to make the reference to agents of actions incomplete or indefinite: indefinite pronouns, passive forms, indefinite personal constructions, subjectless constructions, long form participles and general nouns.

In this work I will describe the use of only four of the above sub-strategies.

Indefinite pronouns

A substrategy of indefinite pronouns («какой-то» — «someone», «почему-то» — «for some reason», «что-то» — «something», «кто-нибудь» — «anyone», «как-то» — «somehow», «куда-нибудь» — «somewhere», «чего-то» — «somehow», «кому-то» — «somebody», «где-то» — «somewhere», «какой-нибудь» — «anyone», «кто-то» — «someone») is found on almost every page. These pronouns create an atmosphere of uncertainty and doubt in the text: are the events and people being described real or unreal?

There are several examples of the use of the pronouns without identifying the agents of the action:

1. Poplavsky, Berlioz's uncle comes from Kiev to Moscow and comes to the House Committee to inquire about the possibility of inheriting Berlioz's flat. At this point «вошел какой-то гражданин [...] что-то прошептал» (р. 466) — «a man walked into the room [...] the newcomer whispered something to him» (p. 167). The man Poplavsky was talking to left and never returned.

2. When Nikanor Ivanovich's wife opens the door to two men who later take her husband away, she is described as «почему-то очень бледная Пелагея Антоновна» (р. 368) — «for some reason very pale Pelageia Antonovna» (p. 84).

3. In Nikanor Ivanovich's dream the audience is warned what will happen if they do not turn in their foreign currency: «с вами случится что-нибудь в этом роде, если только не хуже» (р. 453) — «something like this, if not worse, will happen to you» (p. 137).

The above examples demonstrate how Bulgakov uses pronouns without establishing their referents in order to intermingle, converge and possibly confuse the natural and the supernatural in the novel.

Just as «umbrella terms» defocus the agent of actions, the Russian language has various strategies which defocus the agent — passive forms, subjectless constructions, etc. The use of all these strategies in the novel proves that the same definition can be applied to both language and a text; both can be viewed as a complex system of systems used by humans to communicate. The focus can be shifted away from agents with the help of impersonal constructions (their common feature — unmarked for agents). I assume that Bulgakov uses passive forms, indefinite personal constructions, subjectless constructions and long form participles / pronoun + verb to demonstrate that the absence of the agent of the actions is as significant as its presence. The unmarked forms are used in the novel as marked forms because the reader is almost sure that this agent stands for the secret police.

Passive forms

«Emptying» of the subject is achieved with the help of passive forms of the verbs. The purpose of passive constructions is to remove and de-focus the agent or subject (usually animate) of the sentence.

Below is a limited number of examples which illustrate the shift away from agents, thus, the reader has to decide who the real doer of the actions is: the diabolic forces or the secret police.

1. «Никанор Иванович был доставлен в клинику» (р. 429) — «Nikanor Ivanovich was taken to the clinic» (p. 134).

2. «Были приняты меры, чтобы их разыскать» (р. 613) — «Measures were taken to find them» (p. 284).

3. «Прибавились данные» (p. 610) — «Evidence was added» (p. 282).

4. «Были обнаружены Никанор Иванович Босой и несчастный конферансье» (р. 607) — «Nikanor Ivanovich Bosoi and the unfortunate MC were discovered» (p. 285).

Indefinite personal constructions

The focus can be shifted away from agents by using passive forms, as well as by using the third person plural verb form without a subject which is called in Russian неопределено-личная форма — the indefinite-personal form. Below are examples of indefinite personal constructions:

1. «Василия Степановича арестовали» (p. 463) — «Vasilii Stepanovich was arrested» (p. 164).

2. «Без всяких звонков квартиру посетили» (р. 427) — «(they) visited the apartment without calling first» (p. 132).

3. «За столом уже повысили голос, намекнули» (р. 428) — «On the other side of the desk (they) had already raised (their) voice, dropped (their) hints...» (p. 133).

4. «На Садовую съездили и в квартире 50 побывали» (р. 429) — «[...] they made a trip to Sadovaya street and paid a visit to apartment No 50» (p. 134).

The above constructions contain additional information that the agent of the actions is human. The reader understands that the natural agent, as well as the logical subject of indefinite personal constructions, is the secret police.

Subjectless constructions

In addition to passive forms of the verbs and indefinite personal constructions, «emptying» / defocusing of the subjects can be achieved with the help of the subjectless constructions. In this case the infinitive is embedded in a subjectless construction. The following examples create an atmosphere of uncertainty and doubt in the text — who is the real agent of these actions?

1. «Легко было установить» (p. 607) — «It was simple to determine» (p. 284).

2. «Слышно было, как барона впустили» (р. 610) — «(one) could hear the baron being let in» (p. 287).

3. «Было известно уже, кого и где ловить» (р. 609) — «It was already known for whom to look and where» (p. 286).

4. «Материалу прибавилось» (p. 609) — «material was added» (p. 286).

5. «Пришлось возиться [...] разъяснять необыкновенный случай» (р. 607) — «(it) was necessary to work [...] to clear up the unusual incident» (p. 284).

The use of incomplete or indefinite references to agents creates a mysterious atmosphere in the novel; the reader is not sure about the explanation of the events and has to decide whether the things happen due to supernatural forces, or whether it is the secret police that is the natural agent in most of these sentences. The indefinite or incomplete references to the agents would seem to imply that either the agents are of minor importance or their identity is unknown. However, Bulgakov achieves the opposite effect: the reader understands that the absence of a reference or an indefinite reference to the agents of the actions can be as significant as a definite reference to the agents of the actions.

I have tried to demonstrate how language defined as a systems of systems revolving around the notion of the linguistic sign used by human beings to communicate (different systems of language: phonemes, roots, words, word systems, phrases, contexts, etc.) supports the message of the novel — an interconnection of the natural and the supernatural, sometimes to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish between them.

As a result, Bulgakov creates a surrealistic picture of «the reality», where one does not know what is good and what is bad; a reality in which real / natural, fantastic, satirical, and mystical elements are closely interwoven.

The natural and supernatural events are so closely interconnected in The Master and Margarita that we cannot trace the evolution of the supernatural (i.e. natural events at the beginning, combination of the natural and the supernatural in the middle, and the supernatural — in the end), which would have made the analysis linear and therefore, simpler. That is why the various critical discussions have already shown the impossibility of one single interpretation of the novel, its message, and its characters.

I do not claim that my analysis of the language of the natural and the supernatural within Bulgakov's novel is complete or / and that I have exhausted every option related to the application of the theoretical and methodological principles of a sign-oriented approach. However, I would like to believe that this work will be a step in the direction to a better understanding and appreciation of the novel The Master and Margarita. I also hope that this work can be viewed as a further step to an implementation of a sign-oriented approach on the textual level.

Примечания

Inessa Roe-Portiansky — Ph.D., Kaye Academic College of Education, Beer-Sheva.

1. Josef Conrad, Under Western Eyes.

2. «We are born to turn fairy tale into reality, to conquer space and time». The lyrics to the song The Aviators' March (Марш авиаторов), 1922 and the theme of the 17th Communist Party Congress, Moscow 1934.

3. I. Roe-Portiansky, The Natural and the Supernatural in the Prose of Michail Bulgakov. Ph. D. dissertation, Department of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev 2005; I. Roe-Portiansky, Y. Tobin, A Phonological Analysis of the Lexicon of a Literary Work, In: Linguistic Theory and Empirical Evidence, Bob de Jonge and Y. Tobin (eds), Amsterdam 2011, p. 267—291.

4. E. Aphek, Y. Tobin, Word Systems in Modern Hebrew: Implications and Applications, Leiden — New York 1988.

5. E. Andrews, Markedness Theory: The Union of Asymmetry and Semiosis in Language, Durham 1989.

6. Y. Tobin, Front Sign to Text: A Semiotic View of Communication, Amsterdam — Philadelphia 1989; idem, Invariance, Markedness and Distinctive Feature Analysis: A Contrastive Study of Sign Systems in English and Hebrew, Amsterdam — Beer-Sheva 1994/1995; idem, Phonology as Human Behavior: Theoretical implications and clinical applications, Durham — London 1997; idem, Comparing and Contrasting Optimality Theory with the Theory of Phonology as Human Behavior, «The Linguistic Review» 2000, № 17, p. 291—301.

7. The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, ed. B.G. Rozental, New York 1997.

8. А. Терц, Литературный прогресс в России, «Континент» 1974, № 1, p. 143—190.

9. The lyrics to the song The Aviators' March.

10. F. de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics, edited by C. Bally, A. Sechehaye, in coll. with A. Riedlinger, trans, annotated R. Harris, Duckworth 1983 (1916).

11. Е. Эткинд, Советские табу, «Синтаксис» 1981, № 9, p. 3—20.

12. F. Miller, Folklore for Stalin, 1990, № 81.

13. A. Sinyavsky, Soviet Civilization, New York 1988, p. 193.

14. E. Aphek, Y. Tobin, Word Systems in Modern Hebrew...

15. The examples and the quotation from the novel The Master and Margarita are taken from: М. Булгаков, Мастер и Маргарита, Москва 1988 (the page is mentioned in brackets); M. Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita, Translated by D. Burgin & K. O'Connor, Great Britain. Picador 1995 (the page is mentioned in brackets).

16. E. Aphek, Y. Tobin, Ward Systems in Modern Hebrew...

17. E. Aphek, Y. Tobin, The Semiotics of Fortune-Telling, Amsterdam — Philadelphia 1990.

| Предыдущая страница | К оглавлению | Следующая страница |